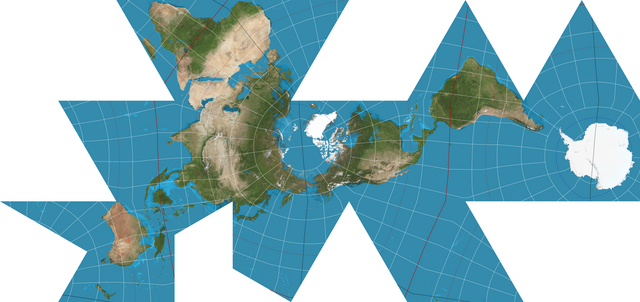

The most famous photograph of Earth was taken upside down.

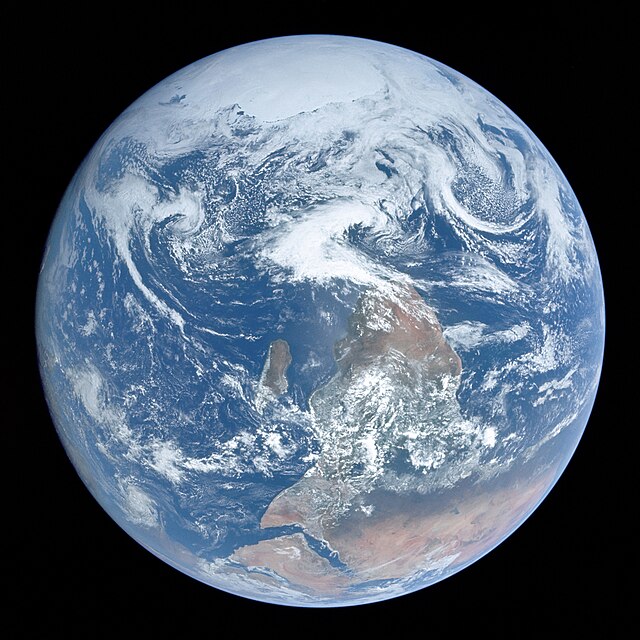

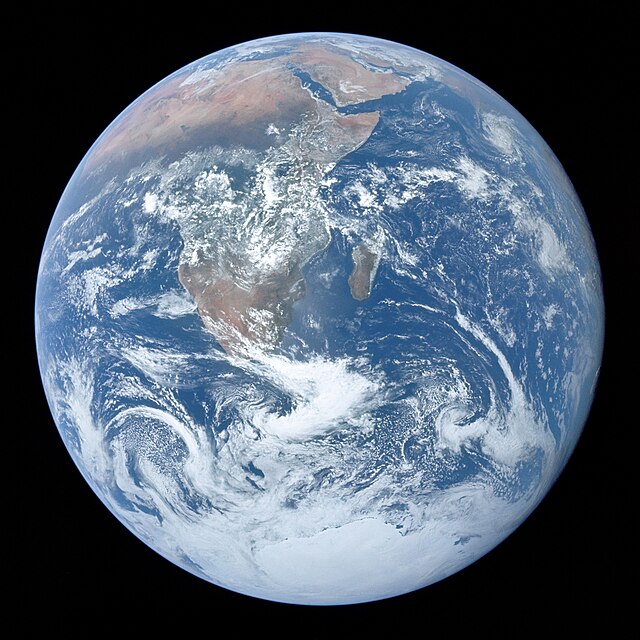

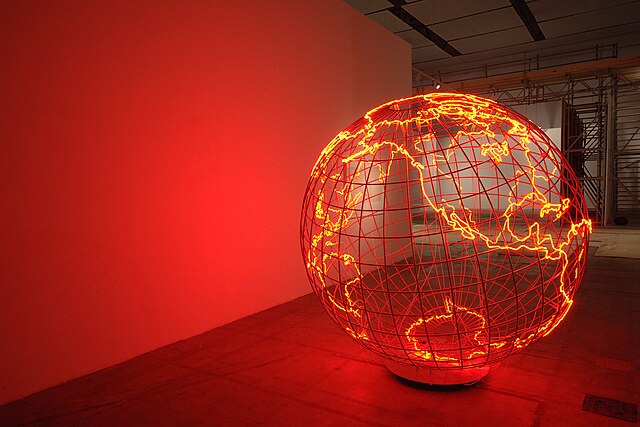

On 7 December 1972, the crew of Apollo 17 photographed the whole Earth from 29,400 km. In the original frame, Antarctica gleams white at the top. Africa stretches to the right. A cyclone churns in the Indian Ocean. This is what Earth actually looks like from that angle.

NASA rotated the image 180° before releasing it. South-up felt “wrong.” The planet itself had to be corrected to match our maps.

No one has been far enough from Earth to take this photograph since.